Everyone is aware of the obstacles that have arisen from public life grinding to a standstill in the wake of COVID-19. It is sometimes more difficult to be aware of the opportunities that can emerge out of these strange conditions. But restrictions in outwards circumstances are always an invitation to journey inward, and to tap into spiritual and intellectual resources that may previously have been unrealized.

At least, that is what the German Catholic philosopher, Josef Pieper (1904–1997), would likely say to us, if he had lived long enough to experience these strange and turbulent times.

Pieper worked in an era when continental philosophy was becoming increasingly truncated to merely linguistic and categorical problems detached from the human, the artistic, and the cultural. He went against this grain by drawing on an earlier philosophical tradition stretching back to the ancient Greeks and running through to thinkers such as Thomas Aquinas. In this ancient tradition, there was no distinction between philosophy and psychotherapy, because competing philosophies each held their own idea of what constituted human flourishing. These thinkers understood that we are philosophers in order to be better humans.

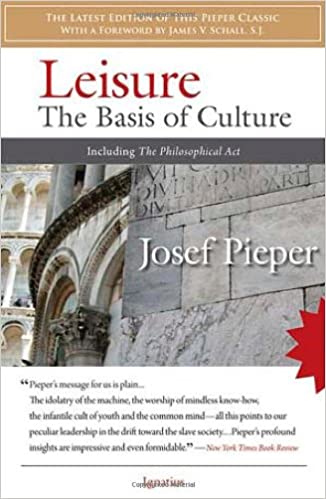

Pieper applied himself directly to the question of human flourishing in his best-known work, Leisure, the Basis of Culture.

The Leisurely Philosopher

Originally published in 1952, this short book was Pieper’s response to moves in the post-war era towards a society of “total work.” In the emerging prosperity of post-war capitalism, no less than the collectivist visions of Marxist societies, human flourishing was coming to be defined by work. There was a corresponding danger that rest would come to be seen as simply the cessation of labor, valued for its restorative function in enabling man to return to work. For still others, rest offered an opportunity for recreation, as if the purpose of work is simply to buy time for play.

Pieper argued that the answer to all of these—the cult of total work, the notion that we rest in order to eventually get back to work, or the infantile cult of youth with its idolizing of recreation—is the idea of leisure.

We don’t use the term “leisure” much anymore, and when we do it tends to differ little from idleness or recreation. Yet Pieper taught that the older notion of leisure is more akin to contemplation, to the type of receptive stillness that we might find in the artist or the spiritual mystic. To be leisurely in this older sense is to adopt a frame of mind that is open to the bedrock ordering of things, an attitude of “inward calm,” and a willingness to slow down and listen to the essence of things.

We get a glimpse of the leisurely frame of mind by reading Pieper’s philosophical works. In works like Leisure, the Basis of Culture, or Only the Lover Sings, he combined the contemplative disposition of a mystic with the passionate joy of a child who takes delight in simply beholding the way things are.

Leisure vs. Sloth

Leisure is the natural opposite to sloth, or what the ancients called acadia. The restlessness of both sloth and boredom reflects what Pieper termed “that deep-seated lack of calm which makes leisure impossible.”

Sloth can be hard to recognize in contemporary society because we have an abundance of tools that enable us to be busy while being slothful. If Pieper were alive today, he might well observe that our common recreations and chosen pastimes—not simply computer games, but also constant connectivity and an endless diet of distractions—may sometimes mitigate against work, but they always mitigate against leisure. This observation might be understored by the fact that, in the Middle Ages, sloth was held to be the source for both “leisurelessness” (the incapacity to enjoy leisure) and the ultimate cause of “work for work’s sake.” (This, incidentally, is precisely why, if you have a teenager who remains glued to his phone, you will not solve his underlying malaise by simply making him get a job or forcing the boy to help with household chores, as beneficial as such activities will likely be for him. Rather, the teenager who is glued to his phone needs to first recover the ability to enjoy leisure, especially that aspect of leisure that is most undermined by an environment of constant digital noise, namely a contemplative, receptive frame of mind.)

Leisure, the Liberal Arts, and Recreation

Pieper’s discussion of leisure was closely tied to his understanding of the liberal arts. He saw that leisure offered us something to live for beyond the servile arts, while also providing a necessary precondition to experiencing the freeing quality of the liberal arts. He understood that both leisure and the liberal arts are gratuitous, meaning they do not serve utilitarian ends, but offer themselves as their own reward. (This, incidentally, is where much pseudo-classical liberal arts curricula goes terribly wrong, especially some of the curricula produced by Veritas Press in the first decade of this century. But that will be the topic of a post next month.)

Both the servile arts and recreation are “useful,” in so far as they appeal to ends outside themselves. In the case of work, that external end is productivity, and in the case of recreation, the internal end is personal pleasure. While there is nothing wrong with either work or recreation in their non-totalizing manifestations, leisure remains the more noble pursuit because it draws us to those realities that are intrinsically valuable in and of themselves.

Pieper believed that leisure could be seen in the ancient practice of the festival, now almost completely absent from urban societies. When we lost the practice of the festival—which, from ancient times, always involved the invocation of gods—we have replaced with the modern practices of recreation, which not only ignores the divine, but ignores the human through its restrictive individualism.

While recreation requires little effort but offers little reward (that is to say, it does not reward us by nourishing the soul or making us more human), leisure may require great effort but offers as its rewards those goods that are intrinsic to itself as a practice. The rewards intrinsic to leisure, like the rewards intrinsic to the liberal arts, require us to become the sort of man or woman who is capable of receiving those rewards as rewards-the sort of person who can enjoy those rewards. We might say of leisure what C.S. Lewis said of the rewards of heaven: it is an acquired taste.

Leisure may ultimately offer more joy than mere recreation, but unlike recreation the joy of leisure is organically connected to the practice itself. Just as the enjoyment a man derives from having a relationship with a modest virtuous woman is organically related to the work of becoming virtuous himself, so the benefits and rewards of leisure are organically related to pursuing leisure on its own terms and independent of external ends. This fact alone makes leisure a hard-sell, for just as a man who has not worked to cultivate virtue may find it hard to understand why another man would enjoy having a relationship with a modest woman, so someone who has not taken time to pursue leisure may find it hard to understand why someone else would find joy in leisure.

A Philosopher for our Time

Leisure, the Basis of Culture can speak to us today, especially those of us who suddenly find ourselves with more time on our hands than we know what to do with. Instead of lapsing into sloth, we can aspire towards experiencing leisure.

True leisure—whether it be sitting still, drawing inward, being receptive to beauty without any agenda, or deeply meditating on what T.S. Eliot called “the permanent things”—may feel strange, and may even appear to have the quality of “work” since it runs contrary to our cognitive habits. Yet, as we slow down to surrender to leisure, we enlarge our soul. Thus enlarged, when we do return to the work-place we will be more fully human and more fully ourselves.

Personal Postscript

Here is a picture of me practicing leisure earlier this week.

There is some background to this picture that takes some explaining. Leisure does not come easy for me, and while I am not tempted towards sloth, I am tempted to what Pieper called “total work.” Moreover, my work has been relatively unaffected by the closures caused by the pandemic, and if anything I have been able to leverage recent days by working even longer and harder.

Last Friday I woke up with flu-like symptoms, including respiratory distress and a dry cough whenever I tried to take a deep breath. I didn’t think it was COVID-19, but because I interact with the public in one of my jobs (which the state of Idaho considers “essential”) I wanted to get myself tested so I could feel comfortable going to that job. The red tape for getting tested for COVID-19 makes it quite difficult, but because I am a Cherokee, I was able to drive down to the Indian Reservation and get tested outside normal bureaucratic channels. (Yes, that’s right. I’m a Cherokee Indian, and I even have enough Cherokee blood to run for chief, though I currently do not have aspirations in that direction.)

All weekend I remained at my office in isolation, not even going for walks. The flu symptoms had disappeared the next day, and I realized that my sickness had only arisen because of overwork. Yet I still thought it was prudent to remain isolated until getting my results back, and not to even go outside just in case I was a carrier of COVID-19. The problem with being shut-in, especially for those of us who have our own businesses and can work from home, is the temptation towards total work. Given my own temptations in this area, I greatly value the opportunity to go for walks or spend time with loved ones. During my time of isolation when these outlets were not available to me, I came to realize just how much I depend on walks in nature for keeping my brain fresh and my emotions healthy.

After getting the results on Monday and learning that I tested negative, I enjoyed some much-needed time in the mountains with my teenage sons, where this picture was taken. As I sat by our fire and sipped some cider, my mind turned towards Peiper and the importance of leisure.

Further Reading