This article forms part of an ongoing series aimed to equip students at classical schools with the skills needed to research for their senior thesis. To read the introduction to the series click here. To access all articles in this series, click here.

The father of two daughters had become convinced that the venue, the Comet Ping Pong restaurant and pizzeria, was actually a cover for a sex trafficking ring with links to Hillary Clinton. At the time, this popular conspiracy theory was being promoted by Alex Jones and various YouTube videos.

When Edgar arrived on the scene he fired shots and searched around. But he could not find the children he had come to rescue. Instead, he found an ordinary pizza restaurant, with terrified workers and patrons.

Welch had only recently had internet service installed in his home. As no one had taught him how to perform due diligence on online sources, he easily fell victim to fake news.

Events such as this “Pizzagate” scandal, as it later came to be called, has led to a crackdown in internet censorship. Google has begun routinely removing materials from YouTube that fail to conform to “community standards.” One of my own videos was even removed for contradicting the Google ideology.

But censorship is not the answer. The answer is better education. Everyone who uses the internet needs to learn the skills of critical thinking, and how to apply critical thinking to source evaluation. And that is what this post is about.

Classical Education and COVID-19

In the introduction to this series, I suggested some practical and ideological reasons why classical educators may be predisposed to ignore information literacy when supervising senior thesis. But that may be changing with the advent of COVID-19.

In early 2020, it became impossible to ignore the paradox that while we have greater access to information than ever before, we are also less equipped than ever to interpret and work with information. As the public has been bombarded with an array of contradictory information, conspiracy theories, and fake news, many have found themselves not knowing who to believe, not being able to distinguish fact from opinion, and not being able to tell the difference between information, disinformation, and misinformation. Some have even retreated to a radical skepticism which maintains that all information is just an interpretation, or that it is impossible to know who to trust, and impossible to arrive at objective knowledge.

On the other extreme to this skepticism, the coronavirus pandemic also revealed numerous individuals who thought they knew what was really going on, and who confidently passed on links to alternative news sources without ever performing due diligence on those sources, and not even knowing how to perform due diligence should they have wished to do so.

In many areas throughout America, the deficit in being able to evaluate and analyze information had potentially fatal consequences, as it led some groups to feel justified in disobeying stay-at-home orders put in place to stem the spread of the pandemic.

During the COVID-19 medical crisis, mainstream journalists and politicians showed an equal deficit in source evaluation skills. When Google removes a video from YouTube for “violating community standards,” this is not because they have performed due diligence on the information in the video, but because it goes against the herd instinct. Similarly, journalists routinely employ the term “conspiracy theory” as a method for dismissing ideas out of hand without conducting proper due diligence.

In short, the COVID-19 medical crisis revealed an information crisis. This information crisis was manifested in a significant deficit in information literacy, which scholars generally define as “the ability to search for, select, critically evaluate and use information for solving problems in various contexts.”

During this crisis, we would expect to see classically educated students exhibiting above-average information literacy skills, especially when it comes to using critical thinking to evaluate information. But while all these students have studied logic, the principles of logical thinking often remain sequestered from real-life applications, with the result that some of our best schools are churning out self-confident students who have the illusion of being able to critically evaluate information. But being able to break apart the mood and figure of a syllogism is of limited value if the student has not learned how to apply logical thinking to evaluating a news source, or if the student doesn’t know how to work with controversial information. In fact, without these information literacy skills, a smattering of training in logic can actually be a deficit if it helps foster a baseless epistemic confidence. That is why, whenever I teach logic, I supplement it with critical thinking materials such as the Bluedorn’s book, The Thinking Toolbox: Thirty-Five Lessons That Will Build Your Reasoning Skills, or Alan Jacobs’ book How to Think, or the material I will be sharing in the present post.

Sadly, up until now, the skills of being able to evaluate information online have not been a priority for classical educators, as seen by the fact that it features nowhere on the Classic Learning Test (CLT), or in the fact that senior thesis classes focus almost entirely on writing and rhetorical skills. This is likely to change. The current crisis in information literacy is likely to result in classical schools becoming proactive in teaching information literacy to their students, both in senior thesis class and earlier. Indeed, what we are beginning to realize is that by 12th grade, information literacy is no longer optional, and this is especially true when it comes to working with online information.

The average 12th grader at a classical school will do a significant amount of his or her senior thesis research on the internet. To expect these students to research without giving them the tools for critically evaluating sources, is like sending someone into a forest of poisonous plants and telling them to find something to eat without ever training them to distinguish edible plants. That is why I am offering a toolbox of techniques for evaluating material you find on the internet.

Tool #1: Browse a Website Before Trusting its Content

If you find something on a website that seems helpful, spend some time reading other articles on the same website to get a feel for where they’re coming from. If the source in question is a YouTube video, spend some time watching other videos on the same channel. It can be especially useful to visit the website’s homepage or their “About” page. But don’t be naive in believing a website’s self-description, as some websites may camouflage their true agendas. As you browse the website, some questions you may want to ask include things like the following:

- How is this website funded?

- Is the content on this website written by anonymous people like “staff authors,” or writers and journalists on which you can perform due diligence (for example, by reviewing other things they have written)?

- Is the content on this website market-driven?

- Is the content on this website ideology-driven?

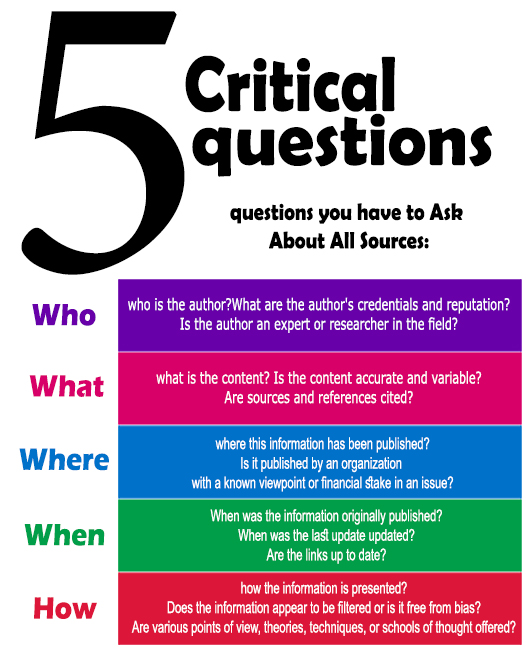

- Ask the 5 critical questions: Who, What, Where, When, and How

Tool #2: Test Information by Checking Multiple Sources

Whenever you find a piece of information online, check to see if it is corroborated by multiple sources. This has saved my skin many times. This is especially true if you suspect something to be a scam or fake. There are enough people writing on the internet now that most scams and fake stories will be reviewed somewhere by someone.

Even genuine information and news can be reported differently on different sites, either because some information is in doubt, or because of differing viewpoints. This is one of the reasons it is always good to triangulate your sources with multiple perspectives, and never trust something from a single source. For example, at the moment there is a video going viral called “Plandemic” which makes startling claims about the origins of COVID-19. Most of the people sharing this video have not bothered to check the claims of this video against other sources, such as the Christian journalist Marshall Allen, who found the Plandemic film to be misleading. We live at a time in history when it is easier than ever to check both sides of an issue, thanks to the Google search engine, and yet many information-consumers never avail themselves of this resource. (For more information on how to do effective Google searches, see my earlier article, “How to Leverage the Power of Google.”)

As you check information by multiple sources, it can be helpful to see what points of agreement exist between those with different perspectives. For example, if there is something that both Republicans and Democrats agree on, then that may require less due diligence than something that only Democrats believe. As you check information against multiple sources, try to distinguish the agreed-upon-facts from the competing interpretation of those facts, while identifying what information those with competing interpretations agree upon.

Consider the following example. In 2017, I wrote an article where I alleged that President Trump had been helping to fortify epistemological relativism in the wider culture. My article relied on a report from then New York Times journalist, Bret Stephens, who cited the President making some troubling remarks that seemed to undermine the concept of objective truth. Following the publication of my article, Republicans were able to dismiss my concerns by pointing out that Stephens is a liberal, while sharing various examples that allegedly proved that Stephens had an ax to grind. Yet a little research would have revealed that the passages I was relying upon, where Stephens quoted the President, were not in dispute, and had been published by other outlets, including conservative sources. If my opponents had done a little research and seen that both CNN and Fox news were in agreement with what President Trump had said, then they could have focused their energy on analyzing my interpretation of those facts rather than needlessly disputing one of my sources.

When you are testing information by multiple sources, look for reviews of entire websites. By looking at website reviews, you can find out crucial information such as whether the website has a history of retractions, or if the website is producing propaganda. Reviews are not always accurate, and must be treated with the same caution as any internet source. But they will help you see both sides of an issue, which brings us to the next technique in our tool-box.

Tool #3: Become Familiar With Both Sides of an Issue

If you are evaluating a source that contains information or interpretations that are potentially contested or controversial, search long enough to become familiar with both sides of the issue. This is especially important if you are deeply invested in a certain point of view, because it is then that you will be most susceptible to confirmation bias. This means that if you are a Republican and you are researching a current political issue, see what the Democrats are saying about the same issue, and if you are a Democrat, then see what the Republicans are saying.

Many people who are deeply invested in a certain way of looking at things may be disinclined to take this advice, and may reply, “but why would I want to explore both sides of this issue when I believe the other side is wrong?” Yet it is precisely when you are most convinced that you are right that it is helpful to review the opposite perspective. Doing this will help you avoid confirmation bias, which is the tendency to interpret information in such a way as to strengthen your preexisting beliefs, and to filter out contrary information, such as new evidence that might weaken your beliefs or theories.

Confirmation bias is as old as sin itself. In the Garden of Eden, the serpent tempted Eve to disobey God by giving her false information, such as “you will not surely die.” Although Eve already had enough information to disbelieve the serpent, she was inclined to believe him because the tree looked pleasant and desirable (Gen. 3:6). This is the first instance of confirmation bias: the tendency to believe falsehood when we have reasons for wanting it to be true.

With the advent of Web 2.0, most of us now consume information that has been curated to fit our individual preferences, personality, and biases. This has the effect of pandering to our fallen tendency towards confirmation bias, in addition to undermining our motivation for learning new things. A good place to begin pushing-back against both these tendencies is to make a point always to become familiar with both sides of an issue, even seeking out sources that you know you will disagree with.

Even when contrary information does not change your mind, it will help you better to understand your own position, or to summarize the views of your opponents with accuracy and charity. (I have discussed this further in my post “How to Listen with Attentive Understanding Even When You Disagree.”)

The Biblical wisdom literature constantly enjoins us to listen to both sides of an issue, and this literature identifies the fool as a person who only listens to the flatterer (a source that tells him what he want to hear). Commenting on the teaching throughout Proverbs that the wise love reproof and the wisdom that arises from it, Dr. Alastair Roberts made the following observation:

“The fool will not carefully consider opposing positions to discover what element of wisdom might lie within them, but will leap at whatever excuse he can find—the tone, the political alignment, or the personality of the speaker, etc., etc.—to dismiss and ignore them. Ultimately, whether he realizes it or not, he hates wisdom, as the task of wisdom is discomforting for him and he will avoid it at all costs. By contrast, the wise will endure considerable discomfort to seek wisdom wherever it is to be found. He will willingly expose himself to scathing rebuke, to embarrassing correction, to social alienation, or to the loss of pride entailed in learning from his sharpest critics or opponents or climbing down from former stances, if only he can grow in wisdom.” (From ‘Wisdom and Folly in Christian Responses to Coronavirus.’)

We will pick up on this theme of flattery again when we consider tool #10.

Tool #4: Check for Spelling and Grammar Errors

The presence of spelling and grammar mistakes is often a dead give-away that you are reading a faulty source, or an amateur publication. Of course, just because something is an amateur publication does not mean that it is false, but at a minimum you would want to dig deeper.

Many people who write fake news intentionally put grammar mistakes into the headlines. See if you can spot the mistake in the headline of this fake news story.

Tool #5: Use Wikipedia and for Fact-Checking

Many of us have professional or ideological reasons for wanting to avoid using Wikipedia, and we can probably all point to situations where we found the online encyclopedia to be in error. Moreover, on controversial subjects like creation and evolution, you can expect Wikipedia to reflect the majority opinion, regardless of whether the majority opinion is accurate or not.

These concerns notwithstanding, numerous independent studies have found Wikipedia to be remarkably accurate for matters of fact. Computer simulations have even proved that it has an effective infrastructure for weeding out “epistemically disruptive agents” (read: disinformers and trolls).

I always recommend people use Wikipedia as a first port-of-call when preforming fact-checks on online sources. It is even a good idea to perform a fact-check on information from a source even when those facts do not directly relate to your research. For example, if you are performing due diligence on a source that claims COVID-19 originated in a Chinese lab, and the source has given wrong dates for the birth of China’s president, Xi Jinping, then this could be a dead give-away that you are dealing with a faulty source, or at least a source that requires a higher level of due diligence. This is where Wikipedia can help.

That said, Wikipedia is not an acceptable source for citing in your senior thesis because it has not gone through the same peer review process that we expect of scholarly publications. There is a type of peer review that happens in Wikipedia, to be sure, and this is quite effective when it comes to raw facts, as Lageard showed with the aforementioned computer simulations. But this is not the same type of peer review that goes into scholarly publications. If one could cite Wikipedia in papers, then theoretically a person without intellectual integrity could edit Wikipedia to reflect some particular bias or error, then quickly quote Wikipedia before the error has been corrected, saying something like “Wikipedia, as accessed on 5/12/20.”

Another reason that Wikipedia should not be cited in your senior thesis is because the standards ensuring good quality prose are very poor. Whatever it’s standards for accuracy, Wikipedia has very low standards for writing quality. Nicholas Carr has collected some examples of very bad prose that has emerged from the online encyclopedia. (The fact that so much work has been done to ensure or prove the factual accuracy of Wikipedia, compared to little to no work on Wikipedia as good literature, reflects the positivist and pragmatic bent of our anti-intellectual culture.)

Tool #6: Look for Context

There are two types of people who browse the internet or ask questions of Google. One type of person uses the grab-and-go approach, getting the answer he or she is looking for and then leaving. The other type of person wants to understand the context surrounding the answer – all the other types of things you need to know before you can make sense of the answer.

For example, it is one thing to look up online and discover that most scientists consider avocados to be a fruit rather than a vegetable, but quite another to understand why this is the case, what the classification system is and when and how it was established, etc.

Context questions are especially important with controversial information. For example, not too long ago a couple friends sent me a viral documentary from the Epoch Times which suggested that COVID-19 originated at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Though the producers of the program clearly have an anti-Chinese ax to grind, some high-quality investigative journalism went into producing this documentary. While watching the program, I kept pausing the video to perform due diligence on their claims. For example, when the program referred to academic journal articles, I looked up the papers. From my very cursory process of due diligence, I concluded that this conspiracy theory might hold some weight, or at least warrant further exploration. But then my mind immediately turned to context questions, which in this case were things like the following:

- How would the release of COVID-19 during a time of peace help further China’s goals of domination in the North Pacific?

- If China is killing her own people with COVID-19, how does that further the aims of the Chinese Communist Party?

- Why would the main researcher at the Wuhan Institute published her research about the receptor protein? Indeed, if she were working for the government as the program suggest, then wouldn’t that research have been classified?

- How has the coronavirus—which has clearly discredited China in the eyes of the international community—helped China’s ambition of gaining Taiwan or destroying America’s military?

These types of context questions are important if we are to apply critical thinking to what we read and watch. Again, contextual thinkers won’t be satisfied with a simple answer—they will want to dig deeper to understand the answer.

I’ll give another example, this time from theology. I have a friend who used to email me quotations from church fathers and saints to prove various theological and political opinions. Being a contextual thinker, I would typically respond to the quotations he would send me with questions like the following:

- Where was this quote published?

- What was the historical context in which this person wrote these words?

- How has this quote been understood in the secondary literature?

Tool #7: Learn to Distinguish Journalism from Curation

It is very hard to evaluate online sources if you aren’t familiar with the difference between curation and genuine journalism. Content curation is the process of sorting through information from the web and organizing it for information consumers. A website like the Drudge Report is content curation. In a sense, someone’s Facebook wall is also content curation. Much of the material on my website here is curated content. By contrast, actual journalism involves researching and reporting on a story directly.

Journalism comes with a high level of ethical obligation that does not regulate outlets that simply curate information from other sources. Many people do not understand this, but in professional journalism the stakes are very high, since one factual mistake can make an entire news outlet liable. This includes mistakes we might tend to think are trivial.

There is nothing wrong with content curation, provided it is not mistaken for actual journalism. There are two reasons why it is important to not confuse curation with journalism.

- content curators do not always perform due diligence on the sources they curate.

- content curators often pose as genuine reporters.

Many of the websites, video channels, and radio programs that promote conspiracy theories are not even curating the work of actual journalists or investigators; rather, they are curating the curators. To actually investigate a conspiracy theory, you often have to work your way backward through layers of curation to find the original story.

An example of a content curator who poses as a genuine journalist is someone like Alex Jones, the conspiracy theorist mentioned earlier who helped perpetuate the pizza-gate scandal. When Megyn Kelly asked Jones about his methods, Jones acknowledged that he simply reports on content his staff find on the internet, without always engaging in first-hand investigative journalism. When you listen to Jones’ show “Infowars”, you are often simply hearing Jones rehash what he has read on the internet. Again, it’s content curation, not investigative journalism, and thus requires a higher level of due diligence from the discerning viewer.

When actual journalists report something that is false, they cannot say (like Jones said to Kelly) that they simply read it on the internet. If you work for a professional journalism company, one mistake can be the end of your career. For example, in 2002 Michael Finkel was dismissed from The New York Times for using multiple interviews to create a composite protagonist for a story on the African slave trade. In 2017 three high level CNN employees were forced to resign after erroneously linking Anthony Scaramucci to a Russian investment fund supposedly being investigated by the United States Senate. I discuss this more in my tutorial video below about fake news.

Journalism is certainly rife with ideology and bias, as manifested in which stories an outlet will choose to cover, how they choose to cover those stories, and the interpretations they offer about those stories. But when it comes to actual reporting of facts, a good deal of objectivity still prevails, as the CNN scandal demonstrates. If accuracy did not matter, CNN would have had no reason to retract the Scaramucci story, let alone to dismiss a veteran reporter, an executive editor, and an investigative editor. The take-home point here is not to be too quick to dismiss the news channels you dislike as “fake news.”

Tool #8: Apply Logic to Source Evaluation

Aristotle identified three ways of persuading people: ethos, logos, and pathos. Ethos relates to the credibility or trustworthiness of the speaker—the aspects in his presentation which shows his character and reliability. Logos relates to the logic or reasoning—the aspects of a presentation that shows rational argumentation. Pathos relates to the emotional appeal—the aspects of a presentation that strikes a chord with the audience and their sensibilities.

Most of the tools we have explored so far have focused on examining online sources according to the criteria of ethos. But it is also important to examine sources according to their logos or logical content.

There are a number of ways logic can help us evaluate sources from the internet, especially sources that integrate information into larger argumentative structures. In my article Logic and Online Source Evaluation, I give multiple examples of how logical tools such as the syllogism and the Square of Opposition can help us evaluate sources. What follows below is a summary of the points made in this longer article.

The presence of routine logical errors, like spelling mistakes, can be a give-away that your are dealing with a source that may need a higher level of external corroboration.At the same time, it is important to distinguish logical flaws in a source from factual flaws. Just as the presence of a spelling-mistake does not render the sentence false, so the presence of logical flaws in an argument does not necessarily render false all the facts within that argument. A discerning internet-user is able to glean information from the premises of an argument even while recognizing when the conclusion the author is drawing from that information may be illogical.Whenever I read something online, I immediately put on my “logic hat” and go through a mental checklist with the following questions:

- Is the writer’s reasoning sound?

- Does this writer’s conclusions follow logically from the information (premises) he or she has presented?

- If this writer’s information is false, then does that render his conclusion faulty, or can each of these be considered separately?

- What information might still be true even if the author’s conclusions do not follow from the preceding premises?

- Is this information in this source logically consistent?

This concern for consistency is a key part of growing in wisdom. Logic prepares the Christian student for wisdom in much the same way that English grammar prepares the student for composing verse. Commenting on the teaching of Proverbs that truth is marked by consistent witness, Dr. Alastair Roberts recently made the following observation:

“The wise are concerned to demonstrate consistency in their viewpoints, as agreement between witnesses and viewpoints are evidence of the truth of a matter or case. However, the beliefs of a fool are generally marked by great inconsistency. They lack the hallmarks of truth because they are adopted for their usefulness in confirming the fool in his ways, rather than for their truth. The fool will jump between inconsistent positions as a matter of convenience. The consistency of the positions and beliefs of fools are found, not in the agreement of their substance, but in the fact that they all, in some way or another, further entrench the fools in their prior ways and beliefs. Also, the intellectual laziness of fools means that they will not diligently seek to grow in a true consistency (although some might develop a consistency in falsehoods designed merely to inure them against challenge, rather than as a pursuit of truth itself).”

Recently I was involved in a situation that showed me just how important this logical foundation to source evaluation is. Many of my friends were inclined towards various conspiracy theories about COVID-19, and they would sometimes send me sources from the internet for my feedback. One friend, whom I will call Bob, sent me a message on Monday claiming that the pandemic originated as a Chinese bioweapon, but by Monday afternoon he had sent me a YouTube video claiming that the pandemic was engineered by Bill Gates so he could profit on sale of a vaccine. On Wednesday morning, I had another message in my inbox from Bob, in which he shared a source claiming that the coronavirus was a hoax because COVID-19 hospitals were actually empty. Because I cut my teeth analyzing the relationships between statements on the Square of Opposition, it was second nature to me to ask whether these sources (all of which Bob presumably believed to be reliable or he wouldn’t have sent them) could all be true at the same time, and how they were or were not consistent with each other.

“I’m curious,” I wrote to Bob, “how all these sources you’re sending me can all be true at the same time? How can the coronavirus be a deadly weapon from China as well as something Bill Gates invented as well as a hoax that doesn’t actually exist? Essentially, you are asking me to believe that Bill Gates manufactured a virus that originated in China that doesn’t actually exist. That isn’t logical!”

Bob is not an anomaly. Many people like him have ideological reasons for doubting the mainstream media, and this will lead them frequently to latch onto competing explanations with no thought of consistency. For example, one minute they will be disputing the role of experts in mediating knowledge to us, only to turn around and promote an expert (whether Jordan Peterson or John Ioannidis) when it happens to suit their political agenda. For these types of unscrupulous informational charlatans, truth doesn’t matter, which is why they are quite happy to simultaneously share inconsistent theories as long as it furthers their agenda of disrupting people’s confidence in the mainstream. This leads us into the next tool, which is the importance of using virtue in how we interact with information.

(By the way, for friends reading this and wondering about the identity of Bob, rest assured that he is not you. He is not anyone because he is a composite drawn from numerous interactions. But in another sense, Bob is all of us – the archetype of what we would all be online but for the grace of God.)

Tool #9: Develop Metacognition and Epistemic Virtue

Sometimes developing best practices for source evaluation is not sufficient if there are mental impediments to right thinking, especially if these impediments are reinforced by the internet. I compare this to sketching a landscape. I can supply an art student with all the right equipment, training, and correct techniques for sketching a landscape, but if the student has an astigmatism, she may not be able to copy anything that isn’t close up , and if she has color blindness, she may not be able to copy colors at all. First I would need to correct the problem so that the student can then take advantage of the techniques I have to offer. Similarly, many of the best practices for online source evaluation cannot be applied because of various cognitive deficits, including,

- The thinking too quickly effect;

- The scattered attention effect;

- The echo chamber effect;

- The confirmation bias effect;

- The bandwagon effect;

- The epistemological bubble effect;

- The Dunning–Kruger effect;

- The over-stimulation effect;

Each one of these effects prohibit proper cognition, with the result that the victim of each effect may find it difficult or impossible to apply the tools I have presented. For example, someone suffering under the thinking-too-quickly effect might take short-cuts and not apply Tool#6 when evaluating a source: instead of reviewing the context to information, the person will simply take a grab-and-go approach. Or again, someone suffering from the echo chamber effect might prematurely assume that a disruptive source is unreliable merely because the source supports the agenda of his or her ideological tribe, without ever getting to the point of applying Tool#3.

Space prohibits us from exploring each of these effects, so I have given some resources below for further study. The point I wish to make here is that once we identify the effect or effects to which we are prone, we can use meta-cognition to push-back against these impediments and achieve the type of cognitive functioning necessary for effective source evaluation.

But what is meta-cognition? Meta-cognition means watching our thinking in much the same way as an athlete might watch his or her body. Metacognition is a way to take control of the cognitive processes that undergird seeking, evaluating, and using information.

By watching his or her body, the athlete is able to notice what training works and what training doesn’t work, and what might lead to injury. Similarly, through meta-cognition we can monitor our thinking when we’re online, catching ourselves when we fall into some of the bad cognitive habits mentioned above. If we find ourselves slipping into the epistemological bubble effect, for example, we can catch ourselves and take measures to restore proper cognition.

To learn about some of the effects that can be combated through meta-cognition, I recommend the following resources:

- Escape the Echo Chamber, by C Thi Nguyen

- How to Think, by Alan Jacobs

- The Role of Stillness in Education and the Problem of Thinking Too Quickly, by Robin Phillips

- Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman

- The Internet and Your Brain, by Robin Phillips

- The Dunning-Kruger effect, on Wikipedia

- Eliminate the Thinking Errors that Hold you Back, by Robin Phillips

So far I have emphasized the role that meta-cognition plays in combating sub-optimal cognitions, which I compared to an athlete keeping an eye out for injury-producing activity. But meta-cognition can also be used in a more positive sense, as a tool for developing various epistemic virtues, which would be comparable to an athlete watching what helps him the most and then focusing on that with greater intensity.

The epistemic virtues are character traits that help with knowledge acquisition and intellectual discernment. These include such things as:

- non-dismissive consideration of arguments;

- charitable interpretation of opposing arguments;

- carefulness;

- being able to weigh up different points of view, including listening to opposing points of view with cognitive elasticity;

- curiosity;

- thoroughness;

- awareness of one’s own presuppositions and potential for being mistaken;

- attentiveness;

- honesty;

- fair-mindedness;

- tenacity;

- love of truth;

- reflectiveness;

- intellectual humility;

- courage;

For some readers, it may not be immediately apparent why some of these virtues help with intellectual tasks, or even why they are virtues at all. In Jason Baehr’s book The Inquiring Mind: On Intellectual Virtues and Virtue Epistemology, he gives an example, drawing on the work of Linda Zagzebski, to demonstrate how virtues like carefulness, thoroughness, fair-mindedness, etc. form an important part of research.

Imagine a medical researcher investigating the genetic foundations of a particular disease. As she conducts her research, she exemplifies the motives characteristic of the virtues of intellectual carefulness, thoroughness, fair-mindedness, and tenacity. She also acts in the manner of one who has these virtues; she examines all the relevant data carefully and in great detail and refrains from cutting any corners; when she encounters information that conflicts with her expectations, she deals with it in a direct, honest, and unbiased way; in the face of repeated intellectual obstacles, she perseveres in her search for the truth.

This example shows how epistemic virtues like carefulness, thoroughness, fair-mindedness, and tenacity are directly related to the intellectual task of working with information and acquiring knowledge. To this we might add further examples more directly related to source evaluation. When I was researching sources relevant to the conspiracy theory about COVID-19 originating in a Chinese lab, I wanted this theory to be false because friends of mine who had promoted it had done so without proper due diligence. I had to use meta-cognition to recognize my own bias, and then apply the virtue of courage to press on with my investigation regardless of what I personally wanted to find out.

Earlier this week I had an occasion to observe how the virtues of humility, honesty, and courage can assist with source evaluation. A friend sent me a YouTube video from the popular “HighImpactVlogs” channel, in which the presenter claims that the pandemic relief bill had been prepared before COVID-19 hit America. (I can’t link to the video because YouTube removed it this morning for “”violating YouTube’s Community Guidelines,” although last night it was still online with over 657,548 views.) This is an intriguing theory for those who don’t trust the government, because it suggests that everything has been unfolding according to a pre-designed script. The narrator in the video adamantly insisted that nothing he shared was his own opinion, and he gave links to primary documents supporting his conspiracy theory.

After my friend sent me this video, I replied in my typical way by saying, “this requires some due diligence.” My friend was taken back. “Due diligence???” he replied. “What do you mean? This person is presenting you facts.”

Well, I wasn’t planning to conduct due diligence on the video, but my friend’s response annoyed me, so I did a little digging. I found that the producer of this video created a follow-up video in which he retracts the first video, admitting that he misinterpreted the evidence. In the retraction video, the producer explains that in order to have a clear conscience before going to bed, he needed to admit that his whole theory had been based on misreading a certain document. “It’s so easy to be misled and it’s also easy to mislead…and that’s what I did in the video before last,” he shared.

A lesser man lacking in the virtues of humility, honesty, courage, and love for truth might have dug in his heels and found a way to defend the misinformation. Or he might have blamed someone else for his mistake. Or he might have buried the new evidence in order to keep collecting revenue from the original video. But this man had enough epistemic virtue to follow the evidence where it led, and to publicly apologize for his mistake. He even renamed the title of his original video to something like “I got this terribly wrong folks.” (I cannot check the exact title because YouTube removed the video this morning.) In his apology video, this gentleman quoted the Chinese philosopher Mencius, who said,

To act without clear understanding, to form habits without investigation, to follow a path all one’s life without knowing where it really leads; such is the behavior of the multitude.

These various examples all illustrate a central concern in the field of virtue epistemology, and that is the role that character and personal dispositions play in the acquisition of knowledge in general, and information literacy in particular.

Intellectual virtues will become increasingly relevant in an environment where we look to Google to organize the world’s information for us. Google has tended to erode dispositions required for cautious research in favor of traits such as confirmation bias, intellectual carelessness, and thinking quickly (have you ever noticed that you think quicker when you’re online than when you’re not?). This poses obstacles toward the type of epistemic virtues that are necessary for effective engagement with information. Unlike simple retrieval methods, which are technique-based and can be taught in a straight-forward manner independent of the students’ dispositions, many of the traits and epistemic virtues needed for adequate reflection with information cannot be taught independent of broader dispositions in a one’s entire life. That is why one of the best things you can do to become a good researcher online is to work to become a good person when you’re offline. This has implications for how we think about younger students, and David McMenemy has rightly suggested that in order to address issues of misinformation and disinformation in the online information behavior of adolescents, we must first address the issue of dispositions and the development of intellectual character.

Tool #10: Grow in Wisdom

I always knew that the book of Proverbs offered principles and guidance for growing in wisdom, but it never occurred to me that this wisdom could help us with online source evaluation. At least, it never occurred to me until Dr. Alastair Roberts published an article using the theology of Proverbs to critique how Christians have been interacting with information during the coronavirus crisis.

Roberts wrote his piece, titled “Wisdom and Folly in Christian Responses to Coronavirus,” after finishing a deep study of the Biblical Wisdom Literature for a course he taught at the Davenant Institute earlier this year. In his article, Roberts expanded on points made in an intriguing video discussion with Dr. Brad Littlejohn about the epistemological crisis generated by COVID-19.

I have already had occasion to cite from Roberts’ article when discussing Tools #2 and #8 above. In closing, however, it would be worth taking a more focused look at Roberts’ insights, especially considering ways that the wisdom of Proverbs can inform our interaction with online information sources.

One of the points that Roberts made is the attitude the Bible enjoins us to have towards experts. The role of expertise is controversial right now, as Tom Nichols has shown in his book The Death of Expertise: The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why it Matters. The widespread skepticism of expertise has led to the bizarre situation of increasing amounts of people considering themselves experts on a variety of pet topics while simultaneously disputing the very notion of expertise. But what does the Scripture’s wisdom literature say about this? From Roberts’ article

“Much of the wisdom literature is addressed to the simpleton, giving the person who lacks wisdom and expertise a nose for wisdom and the character to receive it. It is about gaining an instinct for the shape of wisdom, even before you have developed knowledge or been formed in wisdom yourself. It is how the non-expert conforms himself to wisdom despite his lack of expertise. It is often less about the specifics of what one believes than it is about how you come to and continue to believe it.

But the wisdom literature is also the literature for kings. There might seem to be something of a paradox here, but on closer examination it should make sense. In many ways, the king is called to be the consummate non-expert simpleton. Likewise, wisdom is largely built upon the virtues of the righteous simpleton and never leaves those virtues behind, actually resting more and more weight upon them as wisdom grows.

The wise king is not the universal expert. Rather, he is to be someone with mastery of the task of judgment. And he exercises such judgment well through his gifts in the discerning, taking, and weighing of expert counsel. Ruling with expert counsellors is a rather different thing from rule by experts. Domain-specific expertise and knowledge factors into the wise king’s judgment, but in exercising such judgment he considers and weighs a great many voices of expertise and wisdom before determining upon a specific course of action.

As the wise king is not the universal expert, he must arrive at his wise judgment by some other means, which is a tricky business. And the means by which he does so are largely the same means as those by which the simpleton arrives at any sort of wisdom in the first place, yet developed to a high degree. Because of the vast scope of his responsibilities, the king’s exposure to his non-expertise rapidly grows along with the extent of the obligations for which his wise judgment equips him.

As Scott Alexander observes, the people who were the best at anticipating and preparing for the coronavirus were largely not domain experts, but were people who were attentive to domain experts, while being gifted in the synthesizing of insight from diverse experts and the exercise of prudent judgment in uncertain situations with great risks. This is an important species of wisdom.”

How then does a person acquire the kingly virtue of being able to synthesize insights of experts and make prudential judgments? One way is through a multitude of counselors (Proverbs 11:14; 15:22; 24:6). Again from Roberts’ article:

“The wise surround themselves with a multitude of counsellors. By contrast, fools merely appeal to whatever ‘expert’ will confirm them in their ways, dismiss the experts as agents of a conspiracy or blind servants of an ideological agenda, or absolve themselves from the task of discernment by appeal to the fact that ‘experts disagree’. Fools generally appeal to experts to validate them in their positions, rather than genuinely familiarizing themselves with the scope and shape of the conversation between experts of varying perspectives and insights.

The solitary counsellor is a dangerous thing, as is the clique of unanimous counsellors—whether ‘orthodox’ or contrarian (those who are temperamentally contrarian can often mistake their criticisms of mainstream opinions for genuine stress-testing, while not being alert to the ways that their own positions are open to serious criticisms). True wisdom is to be found in attention to a multitude of counsellors, where the viewpoints of many informed and wise persons are constantly cross-examined, stress-tested, revised, honed, and proven through searching conversation with each other, a conversation often directed by the judicious ruler.

One of the typical hallmarks of cranks is that they simply dismiss peers in the mainstream guild as agents of a conspiracy, as malicious, or as stupid, rather than engaging in sharpening good faith dialogue with them or allowing their work to be cross-examined by them. They will speak of the stupidity of the mainstream experts, without ever closely engaging with them face to face, or truly understanding their viewpoints or arguments. Most actual experts tend to treat other experts who disagree with them with rather more respect.

Another striking feature of Proverbs is the frequent teaching on the relationship between flattery and foolishness. We already touched on this briefly at the end of our discussion about Tool#3. Whereas the wise seek out a multitude of counselors, intentionally exposing themselves to sources that present a variety of viewpoints, the fool seeks out a flatterer who will tell him what he already wants to hear. (The algorithm that regulates the Google search engine is actually structured to pander towards this type of foolish flattery.) Here’s what Roberts writes about flattery in the context of working with information:

The wise recognize that the danger of the flatterer is encountered not merely in the form of such things as obsequiousness directed towards us personally. Flattery also expresses itself in the study or the expert that confirms us in the complacency or pride of our own way, bolstering our sense of intellectual and moral superiority, while undermining our opponents. The fool is chronically susceptible to the flatterer, because the flatterer tickles the fool’s characteristic pride and resistance to correction and growth.

The fool will pounce upon studies or experts that confirm him in his preferred beliefs and practices, while resisting attentive and receptive engagement with views that challenge him (or even closely examining those he presumes support him, as such examination might unsettle his convictions). The fool’s lack of humility and desire for flattery make him highly resistant or even impervious to rebuke, correction, or challenge. You have to flatter a fool to gain any sort of a hearing with him.

Ideology is the friend of the fool. Ideology can assure people that, if only they buy into the belief system, they have all of the answers in advance and will not have to accept correction from any of their opponents, significantly to revise their beliefs in light of experience and reality, or acknowledge the limitations of their knowledge.

By contrast, the wise know that the wounds of a friend are faithful and seek correction. They surround themselves with wise and correctable people who are prepared to correct them. They are wary of ideology.

By surrounding ourselves with flattery, even in the form of websites that reinforce our confirmation bias, we become creatures of the herd:

“The fool seeks company and will try to find or create a confirming social buffer against unwelcome viewpoints when challenged. The scoffing and the scorn I have already mentioned are often sought in such company. The fool surrounds himself with people who confirm him in his beliefs and will routinely try to squeeze out people who disagree with him from his social groups. The fool’s beliefs, values, and viewpoints seldom diverge much of those of his group, which is typically an ideological tribe designed to protect him from genuine thoughtful exposure to intelligent difference of opinion or from the sort of solitude in which he might form his own mind. He has never gone to the sustained effort of developing a pronounced interiority in solitary reflection and meditation, of attendance to and internalization of the voices of the wise, or of self-examination, so generally lacks the resources to respond rather than merely reacting. When the herd stampedes, the fool will stampede with them, finding it difficult to stand apart from the contagious passions of those who surround him.”

Roberts’ entire article is worth reading in full. One take-home point from the article, which makes a fitting summation to our discussion about wisdom, is that none of us should pass on links to information if we have not first performed due diligence on the source we are sharing.

At first, this may seem excessively restrictive. After all, for most of us it has become second-nature to share articles on Facebook and other social media platforms, or to text our friends links to news videos or articles. Rarely do we think to perform due diligence on these sources before sharing. We engage in these types of activities as a form of phatic speech, or to reinforce a sense of victimhood, or to indulge an appetite for the scandalous, or to reinforce political agendas, or because we genuine believe that we can trust this information. If we are challenged (i.e., “did you perform due diligence on this source before sending it to me?”) we typically excuse ourselves by saying something like, “I was just passing on information.”

In Biblical times, “just passing on information,” was considered a species of gossip and the sin of over-speaking. Interestingly, over-speaking is one of the most discussed sins in all of Scripture. Yet we have largely neglected serious thought about how the Biblical teaching about this sin might transfer into the online environment.

My rule of thumb is this: if something would count as gossip in a small village—for example, passing on information that I have not investigated, especially information that is negative towards a certain person or group, or which could incite fear or anger—then that behavior is also gossip in the interconnected digital village we call the internet. Bottom line: don’t pass on links you have not performed due diligence on. Again, from Roberts’ article:

“Fools will readily believe a case without closely seeking out and attending to the criticisms of it (Proverbs 18:17). They routinely judge before hearing. They also attend to and spread rumours, inaccurate reports, and unreliable tales, while failing diligently to pursue the truth of a matter. The wise, by contrast, examine things carefully before moving to judgment or passing on a report.

In following responses to the coronavirus, I have been struck by how often people spread information that they clearly have not read or understood, simply because—at a superficial glance—it seems to validate their beliefs. They do not follow up closely on viewpoints that they have advanced, seeking criticism and cross-examination to ascertain their truth or falsity. And when anything is proven wrong, they do not return to correct it.”

Summary of Tools for Source Evaluation

Let’s close by reviewing the 10 tools of source evaluation that we have reviewed in this article.

- Tool #1: Browse a Website Before Trusting its Content

- Tool #2: Test Information by Checking Multiple Sources

- Tool #3: Become Familiar With Both Sides of an Issue

- Tool #4: Check for Spelling and Grammar Errors

- Tool #5: Use Wikipedia for Fact-Checking

- Tool #6: Look for Context

- Tool #7: Learn to Distinguish Journalism from Curation

- Tool #8: Apply Logic to Source Evaluation

- Tool #9: Develop Metacognition and Epistemic Virtue

- Tool #10: Grow in Wisdom

Further Reading

- “Immune to Evidence”: How Dangerous Coronavirus Conspiracies Spread

- A Classical School’s Guide to Senior Thesis Research, Part 2: How to Leverage The Power of Google

- A Classical School’s Guide to Senior Thesis Research, Part 1: How to Find Information Online

- A Classical School’s Guide to Senior Thesis Research, Introduction: Classical Education and Information Literacy

- Classical Education Archives

Imagine a medical researcher investigating the genetic foundations of a particular disease. As she conducts her research, she exemplifies the motives characteristic of the virtues of intellectual carefulness, thoroughness, fair-mindedness, and tenacity. She also acts in the manner of one who has these virtues; she examines all the relevant data carefully and in great detail and refrains from cutting any corners; when she encounters information that conflicts with her expectations, she deals with it in a direct, honest, and unbiased way; in the face of repeated intellectual obstacles, she perseveres in her search for the truth.

Imagine a medical researcher investigating the genetic foundations of a particular disease. As she conducts her research, she exemplifies the motives characteristic of the virtues of intellectual carefulness, thoroughness, fair-mindedness, and tenacity. She also acts in the manner of one who has these virtues; she examines all the relevant data carefully and in great detail and refrains from cutting any corners; when she encounters information that conflicts with her expectations, she deals with it in a direct, honest, and unbiased way; in the face of repeated intellectual obstacles, she perseveres in her search for the truth.