A couple years ago, while doing some work in London, I found myself with an eight day gap in my schedule. I decided to take the train to the quiet countryside of Essex where I had heard there was a Christian monastery that offered free accommodation to spiritual seekers.

As I sat in the train, watching the English countryside whiz by, I thought of a conversation I had a couple days earlier with the receptionist at the London hotel where I had been staying. The receptionist, a young Italian lady named Francesca, had a sharp elegant-looking Roman nose offset by soft dark eyes. She told me she had immigrated to the UK just a month before, after the severe economic conditions in Italy had forced her to come to London in search of work.

As Francesca shared with me about her homeland, her eyes lit up. She described the pastureland and gentle greenery outside Venice, which had been her home until recently. As Francesca stumbled in broken English to describe the countryside of northeast Italy, I could tell she obviously missed her home and family.

“I’m sorry,” I said sympathetically, “that must be tough having to leave your home and come to a foreign city.” Francesca hadn’t actually told me that things were difficult, but I could sense that life hadn’t been easy of late. I expected her to reply with a comment about her recent struggles, but instead she chose to view these challenges in positive terms.

“I’m just thankful to have a job” she replied in broken English. “Also, I live in Wimbledon where there are some fields and trees, and on my way to work I can look at them to be reminded of my homeland.”

I was somewhat astonished by this reply. Francesca had been uprooted from the land she loved and was facing uncertainty about her future, yet she managed to cheer herself up by looking at fields during her morning commute. She could have interpreted her life in terms that emphasized everything that had gone wrong (the collapse of the Italian economy, leaving her family and friends for an unfamiliar country, moving from the green countryside outside Venice to the crowded London metropolis, etc.) and yet she made a choice to put a positive frame around everything that happened to her.

As if sensing my thoughts, Francesca added, “I decided a while ago, that whatever happens to me, I will keep a positive outlook.”

“You see,” she continued, pausing to find the right English words, “when you have new experiences, you never know what good will come out of them. You never know what you might be able to learn, how you might be able to grow. And, most importantly, you never know how your experiences will enable you to help others later on.”

I was still reflecting on my conversation with Francesca when the train came to a halt. I had arrived at the last station nearest the monastery. The rest of the journey would need to be by taxi.

After finding a taxi-driver who agreed to drive me the rest of the way, and after situating myself comfortably in his car, my thoughts returned to what Francesca had shared. I didn’t know whether Francesca was a Christian, but she seemed to embody verses such as, “having food and clothing, with these we shall be content” (1 Tim. 6:8) or “for I have learned in whatever state I am, to be content” (Phil. 4:11).

Before meeting Francesca, I had always unconsciously assumed that contentment and hardship were related to each other like two sides of a zero-sum transaction. Economists talk about a transaction being a “zero sum game” when the gains of one side are directly correlated to losses on the other side. I had assumed that hardship and contentment were related like this, so that a person could only increase in contentment to the extent that hardship in their life decreased.

At the time, I had been going through a lot of hardship. Not only was I facing a series of seemingly insurmountable problems in my personal and professional life, but I was also suffering from health problems, spiritual doubts and anxiety for people I loved. As I went over and over the problems in my mind, I always seemed to come up with the same answer: I can only be content once God gives me all the stuff I want. After all, I reasoned, the things I want are all good things: I wanted to make more money so I could better provide for my wife and children; I wanted God to bring health and healing to those I loved; I wanted to be more resilient to stress so I could be a better source of stability for my family, and I wanted professional success so I could better minister to people. And on and on. If God gave me all these things, then I could really be content, or so I thought.

But Francesca seemed to represent a different way of looking at the world. Her life was obviously much more difficult than mine and yet she had attained a level of contentment unknown to me. Why was that, I wondered? What is it that enables some people to radiate a sense of peace and joy to everyone they come in contact with, while other people are perpetually dissatisfied, even with the blessings they do have?

While pondering these questions, my taxi arrived at the monastery, nestled in the peaceful countryside of Essex’s Maldon district.

The next eight days were restorative for me. With no technology or cell phone service, I felt like I had travelled back to an era when life was simpler and more peaceful. I spent my days going for long walks in the nearby countryside, resting, joining the monks and nuns in their prayer meetings, and having fascinating conversations with the other pilgrims who came and went.

Almost immediately, I was hooked. The Way of a Pilgrim chronicles the journey of a man who wandered from place to place in nineteenth-century Russian on a quest to learn the mysteries of interior prayer. Inspired by a sermon on Paul’s admonition to “pray without ceasing” (1 Thess. 5:17), the first-person narrator describes his journey to grow into a deeper relationship with Christ through prayer.

A recurring theme in the book is the reciprocity of prayer and gratitude. As if in confirmation to what Francesca had shared with me a few days earlier, the narrator shows that contentment and inner-peace do not arise from having a life free from hardship, but from cultivating a disposition of appreciation for even the smallest blessings.

The trials endured by the pilgrim in the story would be enough to break most of us. He and his wife lost their livelihood and all their money after his wicked brother burned their inn down to the ground. This reduced them to the status of peasants, made worse by the fact that he was unfit for most employment because of being lame in one arm (due, again, to the violence of his wicked brother). He then suffered enormous heartache when his beloved wife took ill and died. The pain of loneliness was so intense that he sometimes wept until he became unconscious. Unable to continue living in a place that constantly reminded him of her, he took to the road to learn the mysteries of prayer. During his travels, the pilgrim became victim to various misfortunes, including almost dying from frostbite, being victim of thieves, enduring inclement weather without anywhere to stay, and even getting whipped because of a false accusation. Being penniless and lame, he often went hungry and subsisted entirely on charitable donations. Though these ordeals tested the pilgrim and often resulted in great sorrow, he managed to become extraordinarily resilient, and even joyful. In fact, this poor and suffering man experienced significantly more joy than most of us will ever know despite all the luxuries of modern life.

How can this be? How can someone be happy in spite of being deprived of so many good things? Again, it comes down to gratitude. A recurring theme in The Way of a Pilgrim is that the grateful remembrance of God can bring peace, calm and joy to any situation, including circumstances that would normally lead to anxiety, stress and grumbling.

The thing that makes The Way of a Pilgrim so inspiring for ordinary people like us is that a positive outlook did not come naturally to the pilgrim in the story but was something he had deliberately to cultivate through reminding himself about God’s blessings, sovereignty and guidance. He often struggled with melancholy, sharing “But at times I felt downcast that I had no permanent place where I could study peacefully and continuously.” He also became downcast by the possibility of starvation and fatigue, and in passage after passage we find him lapsing into depressed feelings and anxious thoughts. But each time he forced his rebellious brain to find something positive to be grateful about. For example, he reflected how his suffering were helping to keep him humble, or how his difficulties might enable him better to understand and help others. He also constantly submitted to the will of God for his life, writing, “I resigned myself to the will of God and once again I was happy and at peace.” Above all, the pilgrim fought mental temptations through continual prayer.

Again and again, the pilgrim had to clear his mind of garbage and learn to be still in the presence of God. He had to continually watch his thoughts, including the narratives he was telling himself about his life. Through constant practice, he eventually became able to interpret everything that occurred through a lens of gratitude.

The pilgrim learned much about living in a constant state of gratitude through reading the Philokalia—a collection of writings from Christian mystics of the Eastern Orthodox church. In conversing with a Christian judge he met during his travels, he shared the following passage from Saint Peter of Damascus, in which the Saint described the attitude of constant joy anyone can experience simply by reminding themselves of God’s blessings:

“It is more necessary to learn to call on the name of God than it is to breathe. The Apostle Paul says that we are to pray without ceasing and by this he means that man is to remember God at all times, in all places, and under all circumstances. If you are making something, you should remember the Creator of all things; if you see light, you should remember Him who gave it to you; if you see the heavens, the earth, and sea and all that is in them, you should marvel and praise God who called them all into being; if you are clothing yourself, remember the blessings of your Creator and praise Him for being concerned about your well-being. In short, every action of every day should cause you to remember and praise God, and if you do this, then you will be praying ceaselessly and your soul will always be joyful.”

When the pilgrim in the story learned to do this—to perceive all of life as a gracious gift—ordinary things began to be occasions for extraordinary delight.

“Not only was I experiencing deep interior joy but I sense a oneness with all of God’s creation; people, animals, trees and plants all seemed to have the name of Jesus Christ imprinted upon them…. When I began to pray with the heart, everything around me became transformed and I saw it in a new and delightful way. The trees, the grass, the earth, the air, the light, and everything seemed to be saying to me that it exists to witness to God’s love for man and that it prays and sings of God’s glory. …in my communion with God I felt as if I were all alone in the world: one great sinner before a merciful and loving God. In solitude I found great comfort, and the sweetness in prayer was much more intense than when I was among people.”

As I went for walks in the fields around the monastery, I reflected what God might be trying to teach me through the Pilgrim’s example, and I also kept coming back to Francesca’s words when she shared, “I decided a while ago, that whatever happens to me, I will keep a positive outlook.”

Ancient Wisdom and Modern Psychology

—Epictetus

Keeping a positive outlook in our mind, like Francesca and the Pilgrim did, can have a direct impact on our emotional health. This is consistent with ancient wisdom, which has emphasized that disordered feelings often arise because of prior problems in thinking and behavior

It may seem common sense that a change in one aspect of the human ecosystem will have an impact in other areas, and that our thoughts, feelings and behaviors are linked in a web of reciprocities. However, throughout much of the modern history of psychology, very little attention was given to the notion of changing maladaptive feelings through addressing thoughts and behavior.

Under the influence of Freud and his successors, much late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century psychology saw feelings as uncontrollable impulses from a dark unconscious, connected to processes of which we are often unaware. In the mid-twentieth century, there was a swing of the pendulum away from Freud as Behaviorist theories began emphasizing only what is observable and measurable. While behaviorism yielded significant insights about the ways that human beings and animals learn and develop habits, it often resulted in a simplistic approach to feelings and thoughts, as if these are merely responses to controlling variables rather than aspects that can be controlled by personal agency (behaviorists like B.F. Skinner actually rejected free will).

In the latter half of the twentieth-century, researchers working within the framework of Cognitive Therapy made huge strides for better understanding the interconnectedness of behavior, feelings and thoughts. Psychologists began to recover the ancient understanding that before effective behavioral modification can occur, there needs to be internal changes of attitude and thoughts, not simply altered variables in one’s external environment. For example, Aaron T. Beck, currently professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania, identified different ways that our thinking distorts reality, contributing to disorders like anxiety and depression.

Despite these advances in psychology, on a popular level many people still perceive their feelings as having a life of their own outside our control. Thus, it’s easy to make a false dichotomy between feelings and skills, assuming that feelings lie completely outside our volition. However, because we are whole people, and because our will, mind and emotions form complex webs of multiple reciprocities, the way to bring transformation in our emotional life is often first to bring our thoughts and behavior into a healthier condition. Both Francesca and the Pilgrim did this by deliberately cultivating thinking patterns rooted in gratitude. In their own way, each strove to be deliberate about the narratives they used when thinking about their situation. In so doing, each was able to transform circumstances of pain into opportunities for beauty and hope.

What Light Are You Viewing Things From?

Rod recounts his first session with a man named Mike Holmes, a Southern Baptist preacher who was also a professional counselor. After hearing about Rod’s story, Mike said that instead of trying to fix the situation, he would help Rod view circumstances in a different light.

“‘…I’m not going to tell you how to fix it,’ he said. ‘But what I am going to do is this. We are going to explore all these stories you’ve told me, and look at them to see where you might be misreading the situation, and where there might be room for positive change.’

‘Here’s what I want you to focus on,’ … You cannot control other people, but you can control your reactions to them.’”

The rest of Rod’s book is a fascinating journey of healing and self-discovery, as he weaves a transparent account of his psychological and spiritual adventures with insights from Dante’s Divine Comedy. As the reader journeys deeper with both Rod and Dante, it gradually becomes apparent that the primary cause of Rod’s sufferings is not actually the discord and misunderstanding in his family but the narratives he was telling himself about those problems.

By the end of the book, all the same problems and misunderstandings still persisted in the Louisiana community. But Rod was able to achieve recovery through learning to perceive the situation in a new light, to move out of a narrative in which he was a passive victim. As he quotes his therapist saying towards the end of the book, “You have power over the images you want to let into your mind. You control them; they don’t control you.”

I’m sure we can all relate to Rod’s struggle. How often do we compound the problems in our life by the narratives we tell ourselves about those problems? Sometimes these narratives are downright false, but more often they are simply incomplete. Often when we think we are simply making an objective observation about a situation, we are actually reacting to the situation as viewed through the lens of a certain narrative. This is especially common in relationship conflict, where one or both members of a relationship may interpret problems through the lens of a distorted or oversimplified narrative about the other. Sometimes these narratives are defense mechanisms that keep us tethered to self-deception, self-justification, victimhood or enabling behaviors.

Thought-Life Inventory

Research shows that much of what we experience in life is fundamentally ambiguous and open to a variety of interpretations. One of the ways we make sense of life’s circumstances is by the meanings we ascribe to those circumstances. The problem arises when we impose meanings onto our experiences that stem from a distorted or incomplete view of reality.

The narratives we tell ourselves have enormous power because of the web of reciprocities linking how we think with how we feel, behave and relate to others. Thus, when problems in your emotional life or relationships start to appear insurmountable, it can be helpful to stop and take a thought-life inventory, asking questions such as the following:

- How might my thought-life be feeding disordered emotions?

- What am I spending my time thinking about?

- Am I dwelling on everything that is wrong in my life, ruminating about the future or engaging in cognitions that make me feel sorry for myself?

- Are the narratives I am believing about myself, my life and my relationships, distorted or incomplete? If I’m not sure, have I made myself accountable to wise people who can help me sort through these narratives?

- What kind of negative self-statements am I telling myself throughout the day?

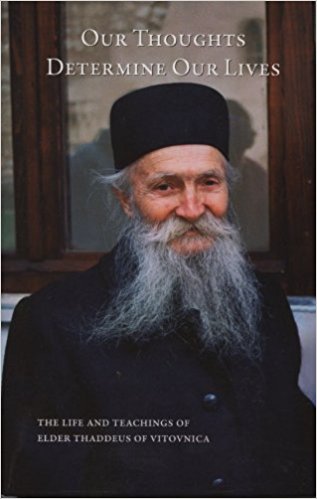

The Serbian Orthodox monk, Elder Thaddeus of Vitovnica (1914-2003) regularly encouraged people to engage in this type of thought-life inventory. Drawing on principles that had helped him to overcome anxiety in his youth, Elder Thaddeus taught people to watch their thoughts and feelings, constantly asking questions like: am I feeling empty or sad right now? If I am, why? What’s going on inside of me?

“Our thoughts, moods and desires set a path for our life” Elder Thaddeus said. He continued, with words that make a fitting conclusion to this postcha.

“Our thoughts reflect our whole life. If our thoughts are quiet, peaceful, and full of love, kindness, and purity, then we have peace, for peaceful thoughts make possible the existence of inner peace, which radiates from us. However, if we breed negative thoughts, then our inner peace is shattered….

“Look at us: as soon as our mood changes, we no longer speak kindly to our fellow men, but instead we answer them sharply. We only make things worse by doing this. When we are dissatisfied the whole atmosphere between us becomes sour, and we start to offend one another.

If our thoughts determine our lives in such a significant way, what can we do to cultivate rightly-ordered thoughts? This is a question I want to explore in a follow-up post where I will be identifying some common thinking errors that lead to disordered emotions and which might be holding you back from realizing your full potential.

Further Reading

- The Life-Changing Magic of Reframing

- Struggle to Find Your True Self

- The Power of Baby Steps in a Superman Culture

- Thinking Errors

“Our thoughts reflect our whole life. If our thoughts are quiet, peaceful, and full of love, kindness, and purity, then we have peace, for peaceful thoughts make possible the existence of inner peace, which radiates from us. However, if we breed negative thoughts, then our inner peace is shattered….

“Our thoughts reflect our whole life. If our thoughts are quiet, peaceful, and full of love, kindness, and purity, then we have peace, for peaceful thoughts make possible the existence of inner peace, which radiates from us. However, if we breed negative thoughts, then our inner peace is shattered….