Part 2 in this series explored research from neuroscience showing that the internet is literally re-wiring our brains, making it increasingly difficult to sustain the type of thoughtful interplay between author and reader that gives book-reading its unique quality. I argued that we are being unconsciously oriented towards a pragmatic view of life that tends to value efficiency above all else. Consequently, our paradigm for learning tends to be based (often unconsciously) on the model of factory production in which everything we do must have measurable and immediate benefits. This makes it hard to nurture the soul through the types of slow and strange magic afforded by books, especially fiction.

Part 3 introduced ideas that I will be exploring more in this latest installment, namely that the erosion of attentiveness has consequences in our capacity to sustain meaningful relationships and to communicate empathetically with people we love. I shared research showing that the skills involved in reading good quality fiction activates the same part of the brain involved in perceiving other people’s mental states – a skill necessary for emotional intelligence, empathy and meaningful relationships.

Since writing Part 3, I have become increasingly interested in the themes I was only dabbling with back in 2013. In this fourth installment, and in a fifth installment to follow later this year, I want to continue looking at the connection between attentiveness and emotional intelligence, while also continuing to identify challenges of modern life that are hollowing out the habits of attention. In particular, the present article aims to establish the truth of the following six propositions:

- Attentive awareness of our own physiological and emotional needs is not subjective psycho-babble, but key to developing self-mastery.

- Emotional maturity involves the ability to watch both our thoughts and our feelings as they occur and thus to increase the gap between stimulus and response.

- The same mental muscles involved in attentive perception of our own moods and feelings are also utilized when we are attentive to others. Ergo, by coming to truly know ourselves, we increase our capacity for knowing others.

- Developing habits of meta-attention, mindfulness and emotional intelligence enables us to exercise the type of self-donation that lies at the heart of Biblical love.

- Loving attentiveness to another person validates their experience and enables them to flourish in their humanity.

- There are many pressures in the modern world that decrease our capacity for sustained attentiveness. However, this can be reversed through specific exercises.

Attention as a Social Virtue

Earlier contributions in this series looked at the threat new technologies pose to an individual’s attention span and focus. This is fairly easy to understand. What is perhaps more difficult to comprehend are the social ramifications of decreased attention. Partly this is because we don’t normally think of attention as a social virtue. Even when we do appreciate the social importance of attention, it tends to be limited to obvious areas, such as the growing tendency to interrupt a verbal conversation to read incoming text messages, or the tendency to go online during a party instead of being attentive to the people in the room.

While we are right to be concerned about the impact these habits are having on social interaction, they remain obvious and easy to comprehend. What is far more concerning, yet perhaps harder to wrap our minds around, is the impact decreased attention is having on our emotional intelligence, on our ability to empathize with others, and on our ability to be emotionally present for those we love.

Emotional Intelligence

Before going further, it may be helpful to define a term that I want to use throughout this article, namely “emotional intelligence.”

Emotional intelligence (EI for short) is a phrase psychologists use to describe the ability to accurately perceive emotions in oneself and others, and to use this information to act wisely. An emotionally intelligent person is able to correctly identify how he is feeling, and to self-regulate his internal states instead of simply being carried away by the latest emotion.

Similarly, an emotional intelligent person is able to accurately identify how other people are feeling in order to empathize with them and be present to their needs.

In both these cases, EI begins with perception—either perception of our own emotions or the emotions of other people. Crucially, however, without attentiveness it is not possible to engage in the type of perception that lies at the root of EI.

From Attention to Perception

We understand the connection between attentiveness and perception if we think about our basic physiological needs. Suppose a young man is so busy scrolling through Facebook or playing on the computer that he doesn’t realize how hungry his body has become and that he needs to stop for lunch, or he doesn’t realize that it’s 2:30 AM and that his body is sending him signals that he needs to go to bed. In such cases, because the man’s attention has been scattered by the latest mental or emotional stimuli, he is unable to perceive what is happening in his body.

Or suppose a girl is so absorbed in a stressful conversation that she doesn’t realize she’s getting a stress-induced headache and needs to pause to take some deep breaths, or maybe that she needs to postpone the conversation for another time after her heart rate has slowed down.

In these cases, total focus on incoming stimuli results in inattention to the body with the consequence that we fail to accurately perceive our own physical needs. Eventually, the person simply reacts to the results of being hungry, or tired, or having a headache, or experiencing stress.

By contrast, healthy individuals are those who are able to preserve enough distance between themselves and incoming stimuli in order to be attentive to their body’s physical needs and make wise choices as a result, instead of reaching a point of simply reacting.

I’m having a hard time learning these lessons in the context of my work. I love to study and write, and I get paid to do so. However, I often get so absorbed in what I’m doing that I forget to pay attention to my body. I forget that I need to take regular breaks to fix a meal or go for a walk or have a nap. The result is that I often drive myself into the ground and then suffer mental exhaustion as a result. By learning to be attentive to my body’s needs, I can pace myself and actually extend my productivity. Then, instead of looking like the miserable person in the left photo below, I can look like the mindful person on the right:

Just as attentive observation of one’s body enable us to make responsible choices and exercise appropriate self-care, so attentive observations of our emotions are important for the same reason.

Everyone experiences emotions, just as everyone experiences physical symptoms like hunger and tiredness, but not everyone pays attention to what they’re feeling. When our attention is scattered by the latest mental or emotional stimuli, we find it difficult to accurately perceive what is happening in our emotional life.

From Perception to Self-Mastery

This is not a plea for touchy-feely introspection. It is appropriate to emphasize that human flourishing involves being outward-looking, forgetting about ourselves and not taking our feelings too seriously. But if this is the case, why did I say it was important to bring attentive perception to our emotional lives? The answer is that healthy individuals are able to pay attention to what they’re feeling, not in order to wallow in their own subjective interiority, but in order to better manage their emotions through productive self-talk.

Observing what we’re feeling enables us to pause, take a deep breath and ask ourselves questions like the following:

- Have I taken something personally that I ought to let go?

- Does my present unhappiness stem from comparing myself to others?

- Is the reason I’m stressed because I’m trying to control a situation I’ve already handed over to God?

- Is the reason a certain person annoys me so much is because there is unresolved hurt?

- In asking questions like this, the goal is to bring self-awareness to our feelings instead of merely being carried away by them. Without this type of perceptive self-knowledge, there can be no true self-mastery.

I’ll share a couple examples from my own life which illustrate the connection between perception and self-mastery. I have confidence in my ability as a writer but feel insecure when it comes to public speaking. Because of this, if someone offers constructive criticism of my speaking skills (i.e., “you said that in a monotone” or “you keep repeating yourself”), I can become defensive and take it personally. I might react by attacking the other person, perhaps with a retort like “I was repeating myself because you gave no indication that you understood” or “you’re just being overly critical.” However, as I gradually develop attentive perception of my own emotional life, I can pause and recognize that the source of my defensiveness is my own insecurity. Once I recognize this the other person is suddenly no longer the enemy, and I can begin constructively talking myself through what I’m feeling instead of simply reacting.

Another example comes from the fact that I’ve recently had some severe setbacks in my academic career. Because of this, when I hear about friends getting teaching positions or having books published, I can sometimes feel envy and resentment. Instead of simply reacting to these feelings and attacking the other person (“she only got that position because she has friends in high places” or “her new book isn’t that good anyway”), I can pause and recognize that the source of my antagonism is envy, resentment and wounded pride. Backing upstream and acknowledging the source of my emotions makes it easier to begin working through these feelings through self-awareness and repentance.

These examples could be multiplied endlessly, but the point is simply this: the way to become free from the prison of self-love, and the way to move beyond our obsession with ourselves, is often to take an honest look at what we’re really feeling. This is a similar principle to how, in the Christian sacrament of confession, the means for being freed from sin is often to look our sin squarely in the eye. By recognizing what we are feeling with honesty, authenticity and mindfulness, we can begin to allow spiritually healthy conditions of feeling (i.e., gratitude, love, peace, joy, meekness) to drive our decisions instead of negative emotions (i.e., grumbling, self-pity, envy, dissatisfaction and desire for worldly things). This type of emotional self-monitoring is crucial in being able to achieve the type of self-rule that the Bible impresses upon us (Proverbs 25:28).

Put another way, getting in touch with one’s feelings is a way to increase the distance between stimulus and response, and thus to cooperate with divine grace in the work of purifying the soul. When there is no gap between something that stimulates our emotions, on the one hand, and our response to that stimulus, on the other, then we remain oblivious to the deeper context for why we react to other people, why we take things personally, and why we allow ourselves to become bitter and resentful over little things. Developing a self-directed emotional intelligence enables us to begin managing and working through what we’re feeling in much the same way that the Psalmists do in many of the melancholy laments. Developing emotional intelligence is a way to recognize—as opposed to simply being carried away by—negative impulses that may not be spiritually and psychologically healthy, or at least may need to be acknowledged and worked through. It’s also a way to recognize healthy emotional states, such as gratitude and compassion, and to make appropriate choices to foster these conditions.

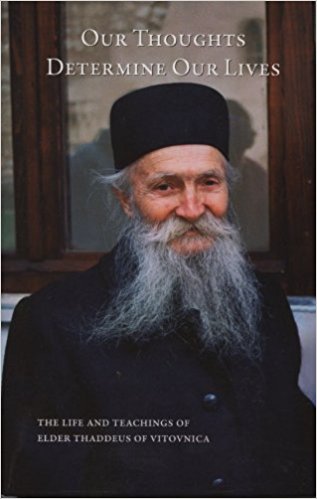

The great twentieth-century Eastern Orthodox monk, Elder Thaddeus of Vitovnica, taught about this to many of the pilgrims who came from all over the world to visit him. He constantly enjoined people to watch their moods, to be mindful to what was happening in their emotional and mental lives. Drawing on principles that had helped him to overcome anxiety in his youth Elder Thaddeus taught people to watch their feelings and to ask questions like “Am I feeling empty or sad right now? If I am, why? What’s going on inside of me?” The Elder’s teachings were later collected together in the book Our Thoughts Determine Our Lives. Here are just a couple quotes from this book about the importance of remaining watchful and observant about our emotional lives:

“

Our thoughts, moods and desires set a path for our life. Our thoughts reflect our whole life. If our thoughts are quiet, peaceful, and full of love, kindness, and purity, then we have peace, for peaceful thoughts make possible the existence of inner peace, which radiates from us. However, if we breed negative thoughts, then our inner peace is shattered….

“Look at us: as soon as our mood changes, we no longer speak kindly to our fellow men, but instead we answer them sharply. We only make things worse by doing this. When we are dissatisfied the whole atmosphere between us becomes sour, and we start to offend one another.” (Our Thoughts Determine Our Lives, p. 71 & 88.)

Be Mindful Instead of Merely Distracted

One of the themes Elder Thaddeus kept returning to throughout his teaching ministry is how the human brain constantly creates its own distractions for us to react to. In every hour the average person experiences thousands of thoughts. Most of these thoughts are completely useless while many of them (i.e., negative thoughts or obsessions about myself) are actually destructive. All too often we involuntarily respond to mental stimuli by taking up each thought and playing with it before another thought takes its place. We engage in this type of mental chatter without realizing it as the mind acts like a constant video screen of one thing after another.

There are numerous reasons why people find it hard to control this constant influx of thoughts. One reason is that many of our technologies train our brains to follow the latest distraction and to accept as normal the condition of continuous partial attention. (I wrote about that in more detail in my Touchstone article ‘Scripture in the Age of Google.’) Even when we are not in the presence of our digital devices, we still retain the neuro pathways forged by so much time with our computers and smartphones since these devices relentlessly invite us to constantly switch our attention from one thing to the next, following the latest stimulus. (See Dr. Caroline Leaf’s observations about the toll that indiscriminate use of technology can take on our ability to exercise attentiveness in general, and see Gary Small and Gigi Vorgan’s observations about how technology erodes our ability to exercise empathy in particular.)

But while our technologies may amplify the challenges we face, the basic problem of the undisciplined human mind goes all the way back to the ancient world. In the 1st century we find Saint Paul encouraging Christians to practice mindfulness through the renewing of the mind (Romans 12:2) and taking every thought captive to Christ (2 Corinthians 10:5). Of course, Saint Paul didn’t call this mindfulness because he wasn’t writing in English, but the principle is the same. (For more about mindfulness and the Bible, see my blog post ‘Mindfulness Craze Catches up with Scripture.’)

Because the mind is closely related to the emotions, most of the things we feel have their origin in our thought life. These emotions are then translated into physiological symptoms such as tightening of the neck, a faster heart-rate and symptoms such as headaches and stress.

Given that our thoughts are the breeding ground of our emotions, it isn’t surprising that our feelings often follow the same jumping-bean pattern as our thoughts. We feel one thing, then another, then another, without always realizing where these feelings are coming from, why we react like we do, or how our emotions can be appropriately identified and managed.

Since the various stimuli we are subjected to (mental, digital, emotional, cognitive and spiritual) exist within an ecosystem of multiple reciprocities, when we allow the gap between stimulus and response to be diminished in one area we are unconsciously encouraging the gap to be truncated in other areas. For example, by pulling your phone out of your pocket to check for messages every 5 minutes, you are weakening the same neuro-mechanisms involved in learning to resist lustful thoughts. Similarly, by putting up no resistance to self-pitying and complaining thoughts, you are weakening the mental muscles needed to resist distractions and be others-centered when a friend requires your full attention.

This might be a good time to pause and take stock of your own experience. Ask yourself the following questions.

- Do you find each second offering new things to pay attention to?

- Are you are constantly sabotaged by incoming emotional, mental or digital stimuli?

- Given the constant stream of new things to pay attention to, do you find it hard to slow down and take stock of how you’re feeling, let alone manage your feelings wisely?

- Do your thoughts run in a constant river of uncontrolled impulses?

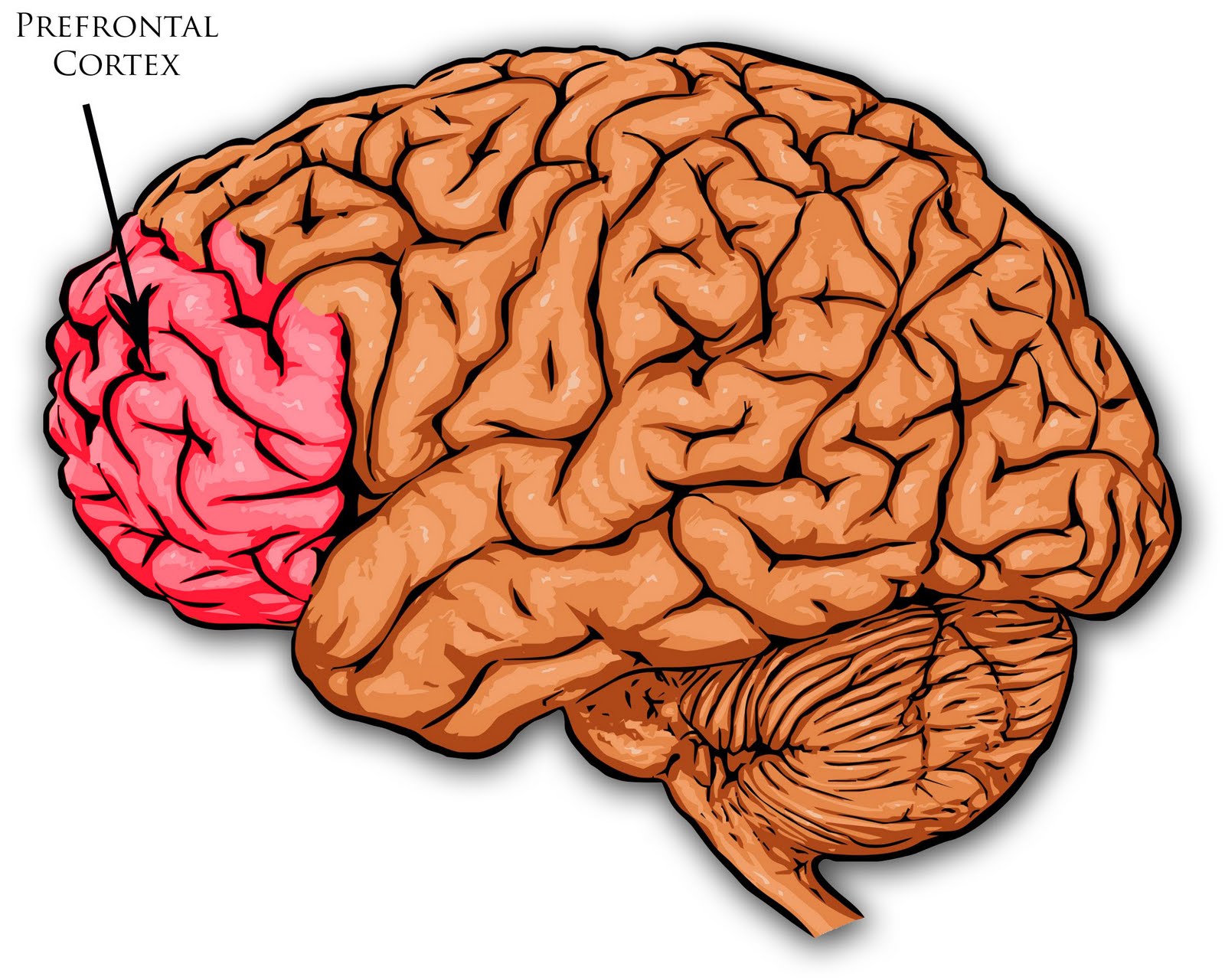

Our goal should be to strengthen the prefrontal cortex through disciplining our minds, taking every thought captive to the obedience of Christ. Only in this way can we weed out thinking errors, slow down the mental chatter, and ultimately develop the type of quiet, gentle, meek thought-life that radiates peace and stillness to those around us. In this way we will be able to imperceptibly pass the kingdom of God onto everyone that comes in contact with us.

But how can we control our brain? Thankfully God has given you a tool for controlling your brain and fasting from toxic thinking. That tool is called the prefrontal cortex. This is the part of the brain that enables you to observe your own thinking. You don’t have to be a brain scientist to use your prefrontal cortex. Every time you watch your own thinking, every time you choose to switch from one thought to another, that’s the prefrontal cortex working.

Christian brain scientist, Dr. Caroline Leaf, has written an entire book about how to bring the mind into obedience to Christ. What Dr. Leaf shows is that the way to conquer the toxic thoughts that lead to depression, anxiety, bitterness and stress, is to develop attentiveness. She shows that our goal should be not merely to pay attention to things, but to pay attention to what we’re paying attention to, in order to control the focus of our emotional and mental lives. But this can only happen when we slow down and choose not to be carried away by the latest stimuli. By being mindful to reject incoming stimuli in order to remain focused on what is good, true and beautiful, we can take stock of what we’re thinking, how we’re feeling, and how we’re behaving. Then we can use practices of mindful attentiveness to regain control of our lives. This enables us to replace toxic thoughts with inner prayer and a constant internal dialogue with God. In her research Dr. Leaf found that doing this actually changes the physical structure of the brain.

“When you objectively observe your own thinking with the view to capturing rogue thoughts, you in effect direct your attention to stop the negative impact and rewire healthy new circuits into your brain…. God designed humans to observe our own thoughts, catch those that are bad, and get rid of them. The importance of capturing those thoughts cannot be underestimated because research shows that the vast majority of mental and physical illness comes from our thought life rather than the environment and genes.” (Switch on Your Brain, p. 72 & 76.)

Long before we had the brain science to back this up, Christian theologians have been saying the same thing. Mystics in the Greek tradition have described this type of meta-attention with the Greek word νῆψις (nipsis), which can be translated “watchfulness.” Saint Hesychios defined watchfulness as “a continual fixing and halting of thought at the entrance to the heart.” (The website for Saint George Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Greenville, South Carolina, has an excellent article on the topic of mental watchfulness which I highly recommend.)

Tune-in Instead of Merely Reacting

One of the benefits of being able to exercise attentive perception of our emotional and cognitive conditions is that we can become better communicators with those we love.

Consider that in many relationships between partners or within families, we can be drawn into conflict over trivial matters that, in and of themselves, should never become matters of provocation, but which become blown out of proportion because they trigger deeper areas of unresolved conflict, hurt, confusion, frustration or insecurity. (I have discussed this in more detail HERE). If both parties in a conflict are working on becoming more attentive to their own emotions, and if they are also trying to lovingly “tune-in” to what the other person is feeling, then during times of conflict they can begin to take a step back and recognize that maybe the real issue behind this conflict is actually deeper feelings that have never been properly worked through or even acknowledged.

This act of stepping back to “tune-in” to someone we love can be difficult since it requires the type of gap between stimulus and response that I was talking about earlier. It invites us to preserve enough distance between ourselves and incoming stimuli in order to be attentive to what is really happening beneath the surface and make wise choices as a result.

If you want to be able to “tune-in” to people you love in this way, a good place to start is learning to be attentive to your own emotions. This is because recent studies about the brain point to a fascinating connection between self-directed attentiveness and others-directed attentiveness. It seems these two things go together since there is a neurological correlation between attentive perception of your own body’s emotions and needs, and your ability to offer attentive perception to another person’s emotions and needs. (Science geeks can explore the evidence for this in the book Neuroeconomics: Decision Making and the Brain, especially page 260, and the journal articles ‘The Neuroeconomics of Mind Reading and Empathy’ and ‘Human feelings: why are some more aware than others?’ and ‘Interoceptive sensitivity and emotion processing: an EEG study.’ There is also a very accessible discussion of this in Chade-Meng Tan’s book Search Inside Yourself, chapter 7.)

Others-Directed Attentiveness

You probably know from your own experience how healing it can be when another person lovingly and attentively tunes-in to you.

Have you ever shared a deeply personal emotion or experience with another person and come away feeling like they just didn’t get it, and that however many different ways you tried to explain yourself the other person just wasn’t connecting with you? Maybe you came away from the conversation feeling stupid and resolving never to open up again.

But have you also had the experience of sharing something with a person who seemed to immediately “get it” without you even having to go into a lot of detail, and who seemed to have an intuitive sense of where you were coming from? Maybe the person was even able to articulate what you were trying to say better than yourself, and helped you to feel validated in the process.

The difference between these two scenarios—the one where you were made to feel stupid and the other where you felt validated—can sometimes hinge on whether we have a personal connection with the person we are talking to, or whether the other person has had similar experiences to our own, but it also has a lot to do with our level of cognitive and emotional empathy. Emotional empathy enables us to feel what another person is feeling even if we have not personally had the same experience, while cognitive empathy enables a person to know how the other person feels and what they might be thinking. Both types of empathy enable us to imaginatively extend ourselves into the other person’s frame of reference, which is ultimately an act of attentive love and self-donation.

But here’s the rub: if our attention is constantly scattered by incoming stimuli, we will find it hard to accurately perceive the needs of those we love, to empathize, or be fully present for others. Ultimately we will find it hard to offer to others the type of self-donation that lies at the heart of Christ-like love. As Elder Thaddeus of Vitovnica observed, “If we listen to our neighbor with only half our attention, of couse we will not be able to answer them or comfort them…. We are distracted. They talk, but we do not participate in the conversation; we are immersed in our own thoughts. But if we give them our full attention, then we take up both our own burden and theirs.” (Our Thoughts Determine Our Lives, p. 95) Because Elder Thaddeus was able to be deeply attentive, people came to his monastery from all over the world to talk to him about their problems.

I know from my own life how important it is for people to listen. I had an experience not too long ago where a good friend phoned me to ask about something that had happened between our children. In the course of the conversation I began opening up about some larger concerns about my children that were causing me to feel anxiety and confusion. As I began sharing what was on my heart, suddenly in the background of the phone call I heard my friend typing. It would be nice to think that maybe he was taking notes about what I was saying, but I knew that in all likelihood he was multi-tasking, dividing his attention between me and an email he was writing. When I realized what was happening I felt so silly and stupid, that I never wanted to make myself vulnerable again. Sadly, however, I have been guilty of the same thing myself—there have been times when my daughter has come to share something with me, and after about five minutes my mind started drifting to think about my work. My daughter still had my attention, but only part of it.

In many other conversations, I might appear to be listening to a friend, but in reality my mind is off thinking about what I’m going to say once it’s my turn to speak again. Being attentive to other people does not come naturally for me, but is something I am struggling to develop. Yet as I grow in this skill, I find an interesting thing beginning to happen. A number of people have started coming to me with their life’s problems because they know I will listen. People don’t approach me with their problems because I’m a touchy feely person; on the contrary, I have often been described as merely a logic-chopping brain with a deficit in basic human intuition. Nor do people come to me because I know how to offer wise advice; on the contrary, I am increasingly trying never to give people advice but to refer people to professionals (priests, therapists, pastors, counselors, monks or nuns). But I am learning to slow down and listen. I know how to say to someone, “The pain you’re experiencing, that’s okay. And even if I don’t know how to help, I’m here for you.”

I’m increasingly convinced that in our age of distractions, inattention and scattered focus, the greatest gift we can offer someone is simply to listen. As Simone Weil once observed “Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.” For many people, the most they can hope to receive is a few “likes” to something they posted on Facebook—a crude substitute for genuine listening. But when we really make ourselves present to another by truly listening, this is healing. It is healing because it assures the other person that she is valuable, that she doesn’t need to feel shame about her vulnerability and pain, and that I love her not in spite of her vulnerability and weakness but because of it. As I explained in Part 3 of this series:

“For relationships to be healthy, we need to know how to suspend what we think and put ourselves in the mind of our friend, even when we think our friend may be wrong. This doesn’t mean we have to pretend to agree with what the other person is saying, but at a minimum we should be able to appreciate where they are coming from, to listen to their heart, to imaginatively relate to experiences that may be far removed from our own. Empathy enables two people who are vastly different to share experiences, to participate in each other’s struggles, sorrows and joys.

To be empathetic requires imagination, creativity, and what psychologists call emotional intelligence. One example of how imagination helps with communication is when it comes to refraining from assuming that what the other person means is what I would mean if I said the same thing; instead we should be able to imagine things from the other person’s perspective. We also shouldn’t be too quick to assume we know what the other person is trying saying, but should be able to say “Is this what you mean?” or “This is how I’m hearing what you’re saying, is that right?” Above all, we should learn to listen non-defensively in a way that helps the other person feel that it is safe to open up…. Healthy relationships require opening ourselves up to another, getting outside of ourselves and entering into the other person’s mind. How many divorces could have been prevented if the parties had only been willing to slow down and work at listening, really listening, to what their partner is trying to say? Such attentive listening is hard work. It is hard work because it requires attentiveness, just like the rewards of reading poetry, listening to classical music, or learning Latin require a similar type of patient attentiveness.

We easily underestimate just how valuable a gift we offer when we simply listen to another person. Conversely, we often fail to appreciate just how much we damage relationships through refusal to listen. This has been proved by Dr. John Gottman, famous for being able to observe a 15 minute conversation between a couple and then predict if their marriage will end in divorce within ten years. Gottman conducted extensive studies aimed to identify the common causes of marital breakdown. He found that one of “the four horsemen” that almost certainly destroys any marriage is stonewalling – refusal to talk and refusal to listen. (In case you’re wondering what the other three marriage-killers are, they are criticism, contempt and defensiveness. Read more about this at the Gottman Institute.) For marriages to work, the husband and wife have to feel the freedom to be able to talk and know they will be heard. (I discussed this in more detail in 2013 when I wrote Part 3 of this series.)

Similarly, the late psychologist Carl Rogers discovered about the power of listening in his work with numerous clients throughout the twentieth-century. In his book A Way of Being, Rogers included an essay about on some of his personal experiences. He described how simply listening to someone was like pulling them out of a dungeon of loneliness:

“I find, both in therapeutic interviews and in the intensive group experiences which have meant a great deal to me, that hearing has consequences. When I truly hear a person and the meanings that are important to him at that moment, hearing not simply his words, but him, and when I let him know that I have heard his own private personal meanings, many things happen. There is first of all a grateful look. He feels released. He wants to tell me more about his world. He surges forth in a new sense of freedom. He becomes more open to the process of change.

“I have often noticed that the more deeply I hear the meanings of this person, the more there is that happens. Almost always, when a person realizes he has been deeply heard, his eyes moisten. I think in some real sense he is weeping for joy. It is as though he were saying, ‘Thank God, somebody heard me. Someone knows what it’s like to be me.’ In such moments I have had the fantasy of a prisoner in a dungeon, tapping out day after day a Morse code message, ‘Does anybody hear me? Is anybody there?’ And finally one day he hears some faint tappings which spell out ‘Yes.’ By that one simply response he is released from his loneliness; he has become a human being again.”

Remember that being present to those we love involves the ability to tune out incoming stimuli (whether mental, emotional, cognitive or digital). Although this is a necessary condition for bringing emotional intelligence into relationships, it is not a sufficient condition. Being attentive to someone involves more than just giving them our time and it even involves more than undistracted listening, as important as these are. Full attentiveness to other people involves being able to achieve a deep calm that can focus on the object of perception. This type of deep attentive perception is both intensive and relaxed; it is focused but also flexible, able to flow and adapt to the object of perception. This type of attentiveness is able to put on hold our preoccupation with ourselves to be fully present for the other person.

At the same time, since a person with EI has developed the habit of self-awareness, he can be in tune with his feelings even while being fully present to the other person. This can be useful in helping us recognize when a conversation may be heading in an unhelpful direction. A person with high levels of EI is able to recognize when an interaction needs to be postponed if it is triggering internal feelings of shame, anxiety or the type of fight or flight response that happens when the amygdala is triggered.

A good analogy for how a person with EI can be fully present to someone else while also being aware of her own feelings comes from both sports and jazz. In team athletic events, or in small jazz ensembles, a participant learns to tune-in to what the other players are doing while still being acutely conscious of her own role. She learns to be fully present and to get herself out of the way simultaneously.

Although we can exercise this type of split attention between ourselves and another person in music and athletics (and perhaps sex should be added to the list), it is very hard in the context of communication. Again, I can speak from experience. If a friend is sharing why something I said bothered him, and in the process he makes sweeping criticisms of my whole experience as a person (or so it seems to me), I am learning to be attentive to my feelings (“wow, this is making me feel really uncomfortable and defensive so maybe I should exercise self-control in how I respond!”), but I find it very difficult to simultaneously be attentive to the feelings of my friend. However, through practicing mindfulness (i.e., being aware moment-to-moment of what is happening in my mental and emotional experiences), it becomes possible to recognize how I am reacting, take a step back, and then tune-in to what my friend is feeling by putting myself in his shoes. By tuning-in to what my friend is saying, I have an opportunity to see the issue through his perspective and then maybe not take things so seriously. I can say to myself things like “yes, the way he’s tearing me down is inappropriate, but there is real pain and deep feeling in what he’s saying, and maybe the best way I can help him is to listen to what’s on his heart.”

Send Your Brain to the Gym with Deep Attentiveness Exercises

This type of attentiveness is a necessary condition not only for truly enjoying other people, but also for being able to enjoy art, literature and classical music, not to mention disciplines of religious piety such as prayer and meditation. All these activities require the type of total surrender that C.S. Lewis described as the first demand of any artwork. In his book An Experiment in Criticism, Lewis wrote that “The first demand any work of art makes upon us is surrender. Look. Listen. Receive. Get yourself out of the way. (There is no good asking first whether the work before you deserves such a surrender, for until you have surrendered you cannot possibly find out.)” The same applies to EI, which involves being able to tune into other people’s feelings to know what is happening inside them even if their experiences are very different from our own. It involves being able to get ourselves out of the way in an act of attentive perception to the other person. (In Part 3 of this series, I looked in more detail at the lab research showing a fascinating connection between reading books and reading people.)

Precisely because of this, one way you can develop EI is by engaging in regular activities that require you to be engrossed in, and surrendered to, something totally outside yourself, such as classical music, poetry, a good quality novel or gratitude meditation. When we engage in these types of activities, we are strengthening the same mental muscles that enable us to offer attentive love to our friends.

If you’ve decided to unplug and read, commit to reading a certain amount before you check your emails. Of if you decide to mindfully listen to classical music, commit to finish a piece before checking your text messages. As you read or listen, practice what Chade-Meng Tan describes as “joyful mindfulness” whereby you bring “full moment-to-moment attention to the joyful experience”. (Search Inside Yourself, p. 70). Every time your focus starts to shift, bring it back to the music or the book. By doing this you will be enlarging your capacity for sustained attentiveness. If you have to do this a hundred times for one piece of music, be encouraged because you’ve just had a hundred training moments.

Another way to increase your capacity for attentiveness is regular meditation. Find a Jesus-based prayer that you can synchronize with your breathing, and commit to doing it for a set amount of time each day. Every time your mind wanders, draw in back to Jesus. You can also spend time focusing on all the reasons you have for being grateful to God. Gratitude meditation is a very effective way to bring your heart rate into a state of coherence and enter a heightened state of attentiveness. (For more about heart-rate coherence, listen to this excellent podcast from Ancient Faith Radio.)

In her book Switch on Your Brain, Dr. Leaf explains how scientific research shows how just five to sixteen minutes a day of “focused, meditative capturing of thoughts” leads to changes in the frontal brain that make a person more likely to engage with the world in positive ways. By applying the Bible’s teaching on mindfulness, one can achieve “deep, intellectual, disciplined thinking with attention regulation, thinking, body awareness, emotion regulation, and a sense of self that changes the brain positively.” (Switch on Your Brain, p. 172)

All these types of activities I’m describing are like sending your brain to the gym, increasing your capacity to achieve a disposition of calm and focused attentiveness. If you practice these skills every day, then when you are called upon to offer deep-attentive-empathetic-emotionally-intelligent-perception to a friend, you will already have strengthened the mental muscles involved. Exercising these mental muscles will also assist you in day to day situations as you find yourself struggling to focus on what is good, true and beautiful and resist spiritually unhealthy thoughts born of pride, self-pity, anxiety and lust.

The analogy of the gym gets to the heart of an important principle, which is that the type of attention that lies at the heart of EI is not something you either have or don’t have; rather, it’s like a muscle that takes years to develop. If you spend years developing the disposition of attentiveness, of quiet focus and of meta-attention, then you will find it easy to be present for others, and you will be able to be like Elder Thaddeus in blessing others with the invaluable gift of attentive empathetic listening.

But you can also spend years weakening your capacity for attentiveness. If you constantly allow your attention to be diverted by the hundreds of random thoughts that come into your head every minute, or by the digital stimuli that constantly bombards us through our smart-phones and other digital devices, then your life will become one of constant reaction and inattention. Under this condition of mind known as “continuous partial attention” it becomes almost impossible to be truly present for those you love, let alone to know yourself with honesty and authenticity. Similarly, if you never use your prefrontal cortex to watch what is happening in your brain, but instead live the unexamined life of beasts, then you will become only a shadow of your true potential.

Further Reading

- Hollowing Out the Habits of Attention (part 3)

- My Pilgrimage Towards Gratitude

- Do What Comes Naturally…But Work at it

- Burdening the Short-term Memory with Distractions

- The Most Important 10 Minutes of Your Life

- Sherry Turkle on Being Alone Together

- Our Disembodied Selves

- Resources on Brain Plasticity

- Posts about Dr. Caroline Leaf’s Work

- Posts About Gratitude

Our thoughts, moods and desires set a path for our life. Our thoughts reflect our whole life. If our thoughts are quiet, peaceful, and full of love, kindness, and purity, then we have peace, for peaceful thoughts make possible the existence of inner peace, which radiates from us. However, if we breed negative thoughts, then our inner peace is shattered….

Our thoughts, moods and desires set a path for our life. Our thoughts reflect our whole life. If our thoughts are quiet, peaceful, and full of love, kindness, and purity, then we have peace, for peaceful thoughts make possible the existence of inner peace, which radiates from us. However, if we breed negative thoughts, then our inner peace is shattered…. “When you objectively observe your own thinking with the view to capturing rogue thoughts, you in effect direct your attention to stop the negative impact and rewire healthy new circuits into your brain…. God designed humans to observe our own thoughts, catch those that are bad, and get rid of them. The importance of capturing those thoughts cannot be underestimated because research shows that the vast majority of mental and physical illness comes from our thought life rather than the environment and genes.” (

“When you objectively observe your own thinking with the view to capturing rogue thoughts, you in effect direct your attention to stop the negative impact and rewire healthy new circuits into your brain…. God designed humans to observe our own thoughts, catch those that are bad, and get rid of them. The importance of capturing those thoughts cannot be underestimated because research shows that the vast majority of mental and physical illness comes from our thought life rather than the environment and genes.” (